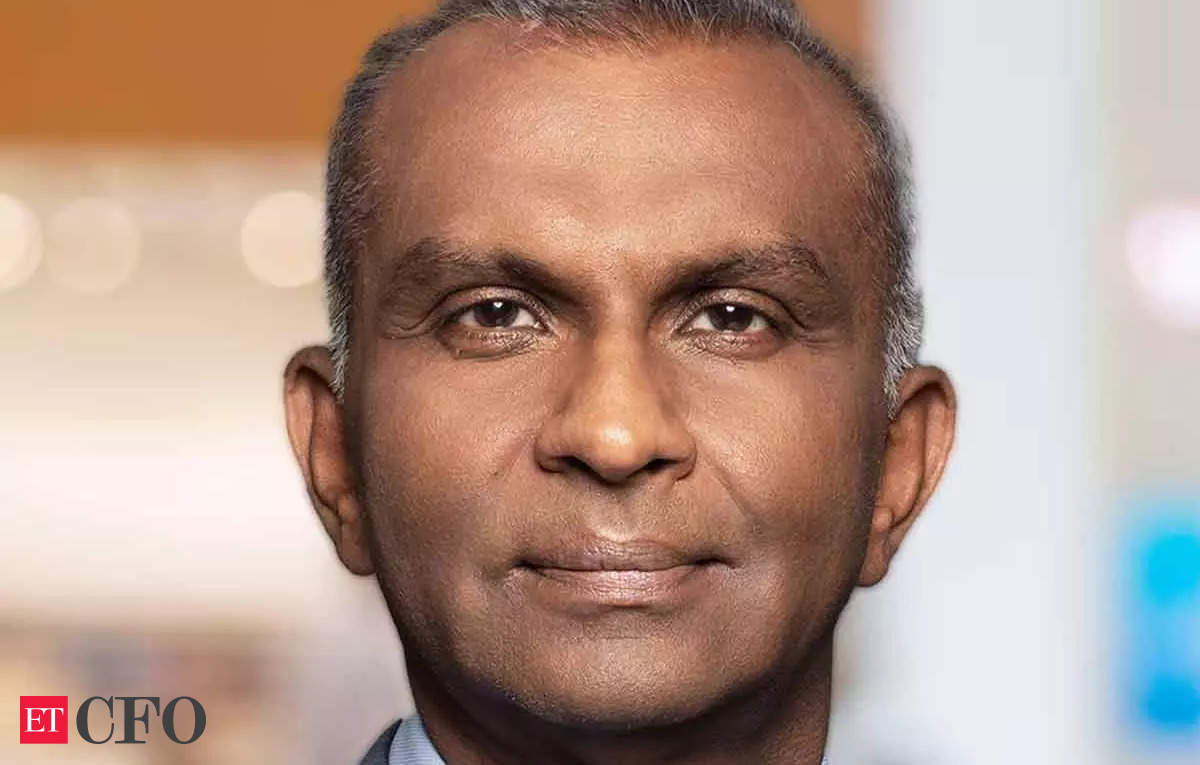

Mumbai: India is expected to be the biggest draw for global investment after the US during Donald Trump’s second term as president, a top Wall Street banker said.

Investors, who have to bet more than $3 trillion, would be picky and there would be a divergence of flows between the public and private markets, driven by return prospects, said Viswas Raghavan, executive vice chairman of Citigroup Inc.

“We have spent quite some time looking at and assessing these flows… The largest market for foreign investment is the US and the second largest market is India,” he said.

As Trump pushes for the US to become a manufacturing hub again, multinational companies are reshaping their investment plans. While policy changes may disrupt the global business order, they are expected to boost U.S. employment.

India, which is a market in its own right and is on Trump’s good side, could be a beneficiary, said Raghavan, who grew up in Mumbai.

Energy, infrastructure and consumer will be the dominant themes for international investors here, even as there is a need to switch to environmentally friendly sources and meet the needs of the huge population, he said.

“The beauty of something like India is that you can produce everything and also consume it,” Raghavan said. “Whereas if you take a UK or another country, you have to send it around.” Rising incomes and unmet demand from the population make India the best market for goods and services, he said.

‘Really ask around valuations’

With the government’s focus on manufacturing, the rise of a new wealthy class and the economy expected to grow at a compound annual rate of 7% – the highest among major markets – investment flows will increase, Raghavan said. “The question is really about valuations,” he said. “In almost three to four years, we’ll see earnings not being supportive.”

Indian equity markets have delivered the best returns among emerging markets in US dollar terms over the past two decades, while growing profits. But that appears to have hit a wall: Portfolio investors have sold a record $13 billion in the past two months as valuations of more than 22 times full-year earnings look expensive, with earnings growth faltering.

Booming prosperity and banking reforms have also helped Indian companies deleverage and lead the way on the global stage, creating opportunities for Citigroup to rebuild its business, Raghavan said. His presence at the top could accelerate this.

“Now we have companies that are absolutely best in class, that can do a phenomenal job of putting India on the world stage,” Raghavan said. “If someone comes to me, gives me an Indian name and says he wants to do this and that, I don’t have to go and see what the company does. I grew up with a lot of these names. There is no discovery process.”

Pushing consulting business

Citigroup, as part of its global restructuring to improve its profitability, has sold its retail operations in Asia, including India. In most parts of the world it remains an investment bank.

Raghavan, who spent decades at JPMorgan leading its European operations, was hired by Citigroup CEO Jane Frazer to rebuild the corporate banking business.

One of his main agendas is to increase fee income and regain market share in his consulting business. Citi is a laggard among Wall Street firms in this area. Raghavan lays building blocks to regain the lost glory.

“I have three lines of business (corporate, commercial, investment banking). The drive is very much to organize ourselves, and effectively bring these three businesses together and connect them very, very closely,” he said.

After the global financial crisis, all full-fledged Wall Street banks were restricted by regulations from taking disproportionate risks. While peers JPMorgan and Bank of America returned, Citi remained risk-averse in financing clients in high-risk bets such as acquisitions, especially through buyout firms. As a result, Citi’s share of leveraged loans has fallen to less than 4%, compared to more than 12% before the crisis.

Raghavan has taken the first step to reverse the trend by partnering with Apollo Management for a $25 billion credit fund that would also help it finance acquisitions. “The problem with leverage is not the availability of liquidity. You can have endless private credit funds all clamoring for paper. The problem is the supply side, and that’s why we got involved with Apollo, with Mubadala and Athene in it,” he says . said.